Australian clinical guideline for diagnosing and managing acute coronary syndromes 2025

3. Recovery and secondary prevention

3. Recovery and secondary prevention

Following ACS, participation in exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation and person-centred, secondary prevention programs (collectively termed cardiovascular risk management programs) is essential to helping reduce future vascular events and improve quality of life and prognosis [458]. These programs support earlier return to usual activities, including work.

All people with ACS benefit from these programs, including women, older adults, regional and remote residents, First Nations peoples, and people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds [51, 458]. These programs complement the care of general practitioners and other allied health professionals by:

- supporting post-ACS recovery and adopting healthy behaviours (e.g. quitting smoking and/or drug and alcohol use, being physically active, eating healthily and maintaining good mental health)

- providing intensive clinical risk factor education and modification (e.g. managing blood pressure, lowering blood lipids, optimising diabetes management)

- ensuring medication adherence and prescription refills, and facilitating review for actual and potential medicine-related harm, when suspected

- educating people on appropriate management of new or ongoing symptoms post-discharge, including use of anti-anginal medicines and when to seek urgent medical attention

- taking actions to protect against influenza and other pathogens, exposure to climate extremes, severe air pollution and cardiac toxins where applicable

- empowering people and their carers/support people towards greater self-care and management of their underlying cardiac status and comorbidities.

A system-generated referral to a flexible, tailored risk management program should be made before hospital discharge. It is also vital to schedule a post-discharge review with a member of the treating team (e.g. cardiologist, specialist nurse) to address immediate needs such as medicines adherence, wound care and mental wellbeing.

Person-centred non-pharmacological secondary prevention

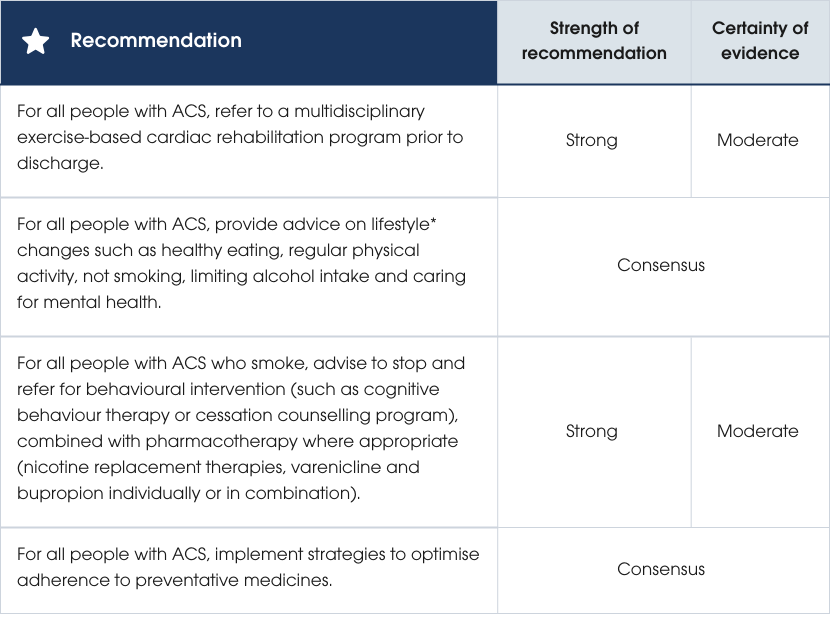

Recommendations

*Use of the word lifestyle here refers to a collective group of modifiable risk factors. The authors wish to acknowledge that these risk factors are not solely dependent on individual choice, and instead reflect the cultural, social and environmental factors that influence behaviour. This term does not in any way attribute blame to individuals.

Evidence supporting the recommendations

Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation can reduce the risk of further MI and all-cause hospital admissions in people post-MI or revascularisation [458]. Exercise-induced cardiac events are negligible in comparison to the risk associated with being habitually sedentary. Similarly, smoking cessation is strongly associated with a lower risk of future MI and death [459–462]. Suboptimal adherence to prescribed medicines following ACS is linked to increased rehospitalisation and mortality [463]. One study found 45% of people with ACS were not taking lipid-lowering medicines 12 months after discharge [464]. Another audit found only 65% of people were discharged on recommended medicines (antiplatelets, lipid-lowering agents, beta blockers and angiotensin-converting enzyme [ACE] inhibitors) [465]. Starting these treatments in hospital and providing clear medicines education are critical to improve adherence [466].Practice points

Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs

- Cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention programs should offer evidence-based aerobic and resistance training in accordance with the current Cardiac Society of Australia and New Zealand Position Statement [467]. Where an exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation program is not available, refer to a flexible, cardiovascular risk management program.

- Evidence-based cardiac rehabilitation programs should be tailored, where possible, to meet the unique needs of groups with low attendance rates, including women and people from culturally and linguistically diverse communities [468, 469].

- For First Nations peoples, enable access to cardiac rehabilitation programs facilitated by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health practitioners wherever possible.

- For people whose first language is not English, enable access to bilingual educators wherever possible.

- For people with ACS living in regional and remote communities, cardiac rehabilitation via telehealth is an acceptable alternative to in-person programs [470]. The Cardiac Services Directory (cardiacserviceslist.heartfoundation.org.au) on the Heart Foundation website lists cardiac rehabilitation programs available throughout Australia, including those delivered via telehealth.

- Embed system-generated referral to a cardiac rehabilitation/risk management program based on a person’s preference, values and the available resources [471–476].

- Consider use of digital health interventions in the delivery of cardiovascular risk management programs post-ACS such as reminders, text messaging, mobile health (mHealth) apps, telehealth consultations, wearable devices and electronic decision-support tools [474, 477, 478].

Lifestyle management

- Provide relevant disease and lifestyle education; the latter covering healthy eating, regular physical activity, not smoking, limiting alcohol intake and caring for mental health. Refer to the Heart Foundation website for guidance and resources on these topics [479].

- Screen people with ACS for depression and other mental health conditions using validated tools and refer for appropriate mental health support as required. People with ACS commonly experience feelings of low mood, sadness, guilt, worry and anger [480, 481].

Medicines adherence

- Provide effective medicines education at discharge. This should include discussion of:

- what each medicine is for, the strength and dose, and when and how to take it

- the importance of continuing to take medicines as prescribed, and not stopping or changing the dose unless advised by their general practitioner

- what to do if they miss a dose

- potential side effects and what to do if they believe they are experiencing a side effect.

- Implement practical strategies to promote adherence, such as daily alerts/reminders, combining medicines where possible (fixed combination medicines) and pharmacy-provided medicine packs.

- Consider post-discharge comprehensive medicine review, particularly in those with significant medicine changes, polypharmacy and/or multimorbidity, those on high-risk medicines such as anticoagulants, and those at risk of medicine non-adherence [482] .

Follow-up care

- Provide a verbal and written discharge summary that includes:

- the diagnosis and treatment, as well as investigation findings

- scheduled follow-up appointments (post-discharge review with the treating team, general practitioner, cardiac rehabilitation)

- medicines commenced, altered or ceased while in hospital, and the importance of taking medicines as prescribed

- healthy lifestyle changes and practical strategies to implement these

- a chest pain/angina management plan.

- Ensure chest pain/angina management plans include guidance on management of new or ongoing symptoms post-discharge, including use of anti-anginal medicines, and when and how to seek urgent medical attention (i.e. calling Triple Zero (000) for an ambulance rather than driving to hospital).

- Two-way communication between the discharging hospital and the person’s general practitioner is critical to support their ongoing care. Similarly, encourage people with ACS to establish/maintain regular contact with their general practitioner for ongoing follow-up.

- Initiate a general practitioner management plan or team care arrangement to assist in the management of comorbidities. This is particularly important for older adults with geriatric syndromes including frailty, impaired cognitive function and polypharmacy [471–476].

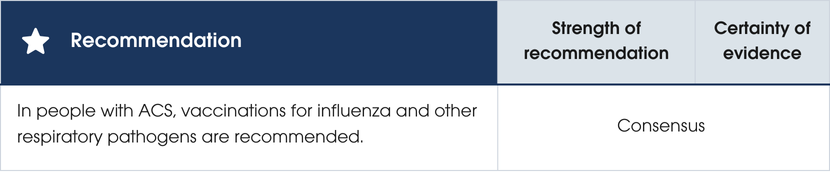

Evidence supporting the recommendations

Practice points

- People with CAD should receive influenza and pneumococcal vaccinations as per recommended schedules [485]. The influenza vaccine can be safely administered within 72 hours of hospitalisation for AMI, including for an invasive coronary procedure [483].

- People with CAD aged ≥60 years should receive RSV vaccination due to their increased risk of severe RSV disease [485].

- People with chronic cardiac conditions, including coronary heart disease, are at increased risk of severe COVID-19 and may benefit from additional doses of COVID-19 vaccine.

Evidence supporting the recommendations

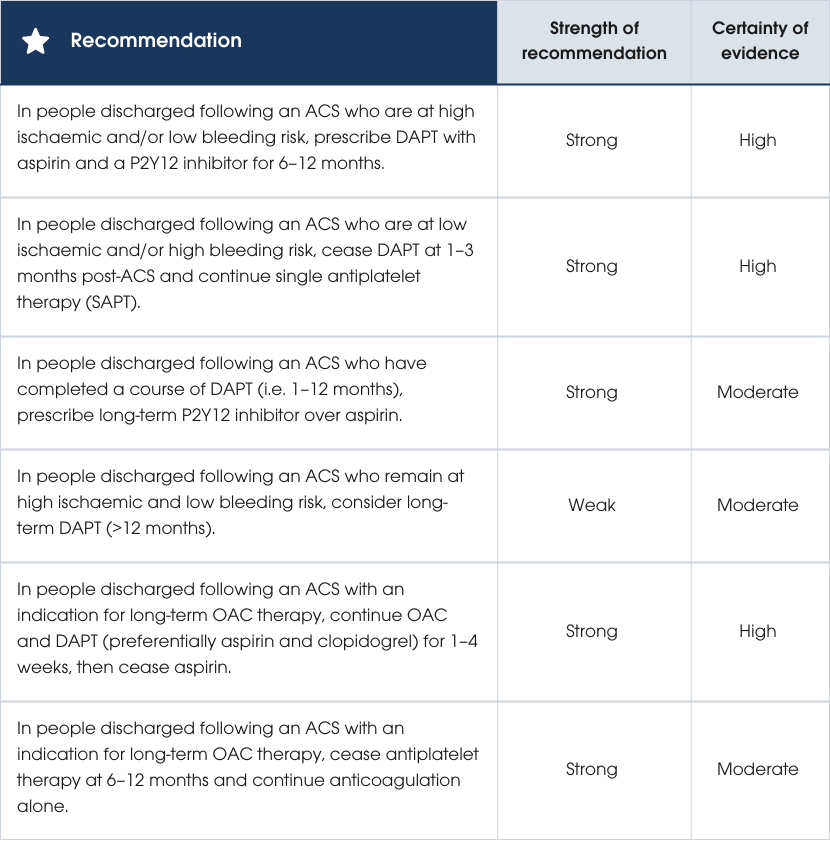

It is important to note that most DAPT trials have focused on people undergoing PCI. Those managed with CABG or medical therapy alone are often only included in subgroup analyses, making it less clear how these recommendations apply to non-PCI groups.

Duration of DAPT in people with ACS

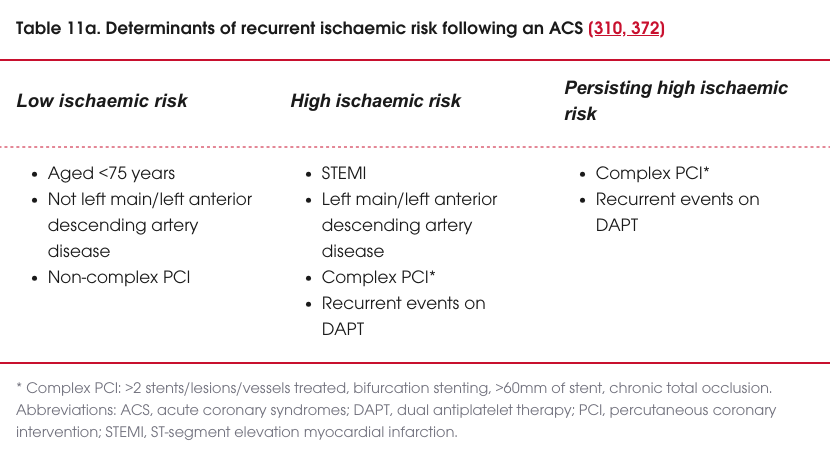

In people with ACS undergoing PCI, shorter DAPT (1–3 months vs 6–12 months) may result in significantly fewer bleeding events, with no major differences in MACE [372]. Prolonged DAPT has also been shown to reduce ischaemic events in people with ACS undergoing PCI, although not in people at high bleeding risk [310]. However, some studies have shown that although prolonged DAPT can reduce the incidence of cardiovascular death, MI, stroke and stent thrombosis, it can increase the risk of bleeding [487, 488]. Latest evidence demonstrates that in people with ACS and those with stable disease undergoing stenting, continuing a P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel or ticagrelor) rather than aspirin may offer the best balance by reducing both major bleeding and the risk of MI [489, 490].People at high bleeding risk

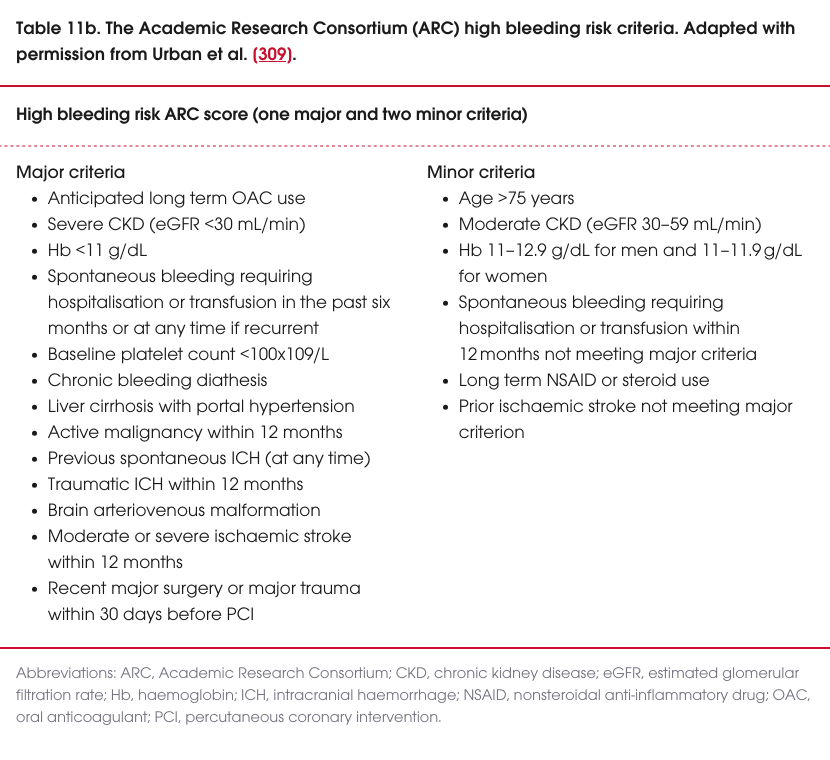

Several scoring systems, such as the PRECISE-DAPT score and ARC-HBR, help identify people at HBR who are receiving DAPT after PCI [118, 491–493]. In people with HBR, shortening DAPT to 1–3 months may reduce major or clinically relevant bleeding without increasing MACE [310, 494] .Long-term SAPT

In people undergoing PCI, SAPT (P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy) can reduce bleeding and provide similar protection against MI compared with DAPT (of 1–18 months duration) [495]. P2Y12 inhibitor monotherapy provides superior protection over aspirin alone, which has been linked to a higher MI risk [495–497]. It should be noted ticagrelor is not currently subsidised on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) as monotherapy. Current PBS criteria state ticagrelor must be prescribed in combination with aspirin.Refer to the Figure 15, Table 11a and Table 11b for guidance on DAPT duration following an ACS.

Figure 15 Decision tree for dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) duration following an ACS. *Prasugrel is not indicated in people who do not undergo PCI.. ¥Refers to the de-escalation of DAPT to aspirin and a less potent P2Y12 inhibitor (clopidogrel). #Current Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme criteria preclude the prescription of ticagrelor as single therapy. Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndromes; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention.

People with atrial fibrillation requiring long-term anticoagulation

A meta-analysis of four DOAC-based RCTs in people with atrial fibrillation undergoing PCI (>50% ACS) found dual therapy (clopidogrel + DOAC) reduced bleeding compared to triple therapy but increased stent thrombosis rates [498, 499]. A network meta-analysis of five studies supported non-vitamin K OAC + P2Y12 inhibitor therapy without aspirin as the safest option compared to regimens including aspirin or vitamin K antagonists [500]. Higher stent thrombosis rates were observed within the first 30 days with dual therapy, suggesting aspirin may be continued for up to one month for people not at high bleeding risk [499, 501, 502]. Continuing a DOAC beyond one year without SAPT showed no effect on ischaemic or bleeding events in people with HBR, while combining aspirin with a DOAC increased mortality compared to DOAC alone at one year [402]. It is recommended to stop antiplatelet therapy after 12 months and continue a DOAC for people with ACS requiring long-term OAC. Refer to Figure 16 for guidance on recommended antiplatelet treatment strategies for people with ACS requiring long-term DOAC for atrial fibrillation [503, 504].

Figure 16 Recommended antiplatelet treatment strategies for people with ACS requiring long-term DOAC for atrial fibrillation. #DAPT: aspirin plus clopidogrel preferred. *SAPT: clopidogrel preferred. Note: People receiving triple therapy should be given a proton pump inhibitor. Abbreviations: ACS, acute coronary syndromes; DAPT, dual antiplatelet therapy; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; SAPT, single antiplatelet therapy.

Practice points

Duration of DAPT in people with ACS

- In older people (≥70 years) with ACS, particularly if HBR, consider clopidogrel as the P2Y12 receptor inhibitor [452].

People at high bleeding risk

- A mobile phone-based application has been developed to assist with decision-making for people at HBR. This is based on an algorithm that predicts risk of major ischaemic and bleeding events [505].

- In people receiving DAPT with high risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, a proton pump inhibitor is recommended.

People requiring long-term anticoagulation

- In people with ACS undergoing PCI with other conditions that require long-term anticoagulation (e.g. mechanical heart valve), a lack of evidence prevents recommendations being made.

- The recommendations in this section can be applied to people with ACS and MI undergoing medical management [371].

- In people who have undergone PCI and are at HBR, de-escalating therapy to anticoagulation alone after 6 months may be reasonable [402].

- In people receiving triple therapy, a proton pump inhibitor is recommended.

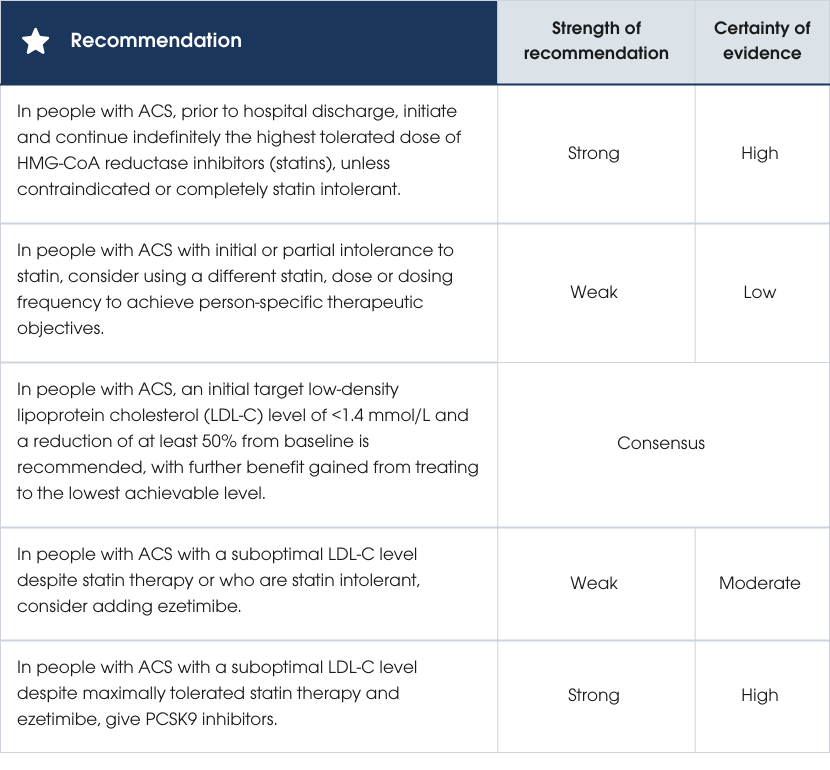

Evidence supporting the recommendations

Practice points

- Initiate or continue high-potency statin therapy (e.g. atorvastatin or rosuvastatin) as early as possible during the ACS admission, irrespective of baseline LDL-C level [506].

- For people on lipid-lowering therapy prior to index ACS admission, consider intensifying existing lipid-lowering therapy.

- Re-assess total cholesterol and LDL-C levels 4–6 weeks after initiating or intensifying treatment. Adjust statin therapy or add non-statin therapy accordingly. Note that additional non-statin therapies are frequently required to achieve target LDL-C levels and to prevent recurrent coronary events.

- In people with ACS (men <55 years and women <60 years), the Dutch Lipid Clinic Network score can guide the need for diagnostic genetic testing. If genetic predisposition is confirmed, consider cascade testing, genetic counselling and initiating statins in family members [510].

- In people with ACS with triglyceride levels of 1.5–5.6 mmol/L and LDL-C 1.0–2.6 mmol/L despite statin therapy, consider adding icosapent ethyl [511]. Note that the current PBS eligibility criteria for icosapent ethyl is a triglyceride level of ≥1.7 mmol/L.

Women

- In women at risk of a major vascular event, commence statin therapy [512].

- Note women are less likely than men to be prescribed statin therapy post-ACS [513].

Older adults

- In older adults with evidence of occlusive vascular disease (such as prior MI), consider statin therapy to reduce the risk of major vascular events [514].

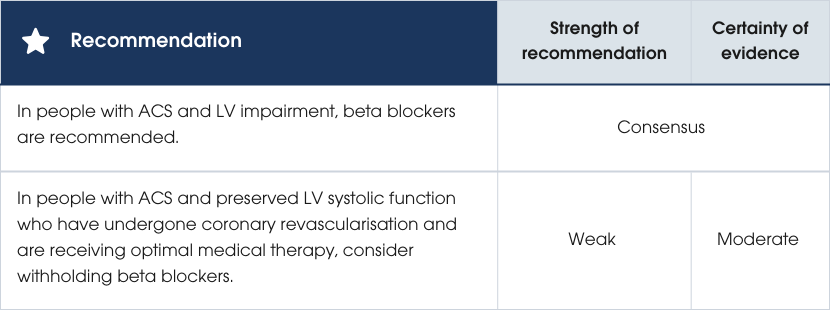

Evidence supporting the recommendations

Practice points

- In people with MI and risk factors for cardiogenic shock, exercise caution when initiating beta blockers as these people may be at increased risk of early mortality [519].

- IV beta blockade in STEMI prior to PCI has not been shown to reduce death or MI at one year [520, 521].

- In people with confirmed LV dysfunction, consider using a beta blocker of proven benefit in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (bisoprolol, carvedilol, metoprolol [controlled or extended release] or nebivolol). See the Guidelines for the prevention, detection, and management of heart failure in Australia for further details including other recommended therapies [454].

- In people with preserved ejection fraction, no benefit in continuing beta blockers beyond 12 months has been seen but more research is being done [522–525].

- In asymptomatic people discharged following an episode of UA (i.e. without MI) and with normal LVEF, there is little evidence for protection against MACE from beta blocker therapy in the absence of other indications.

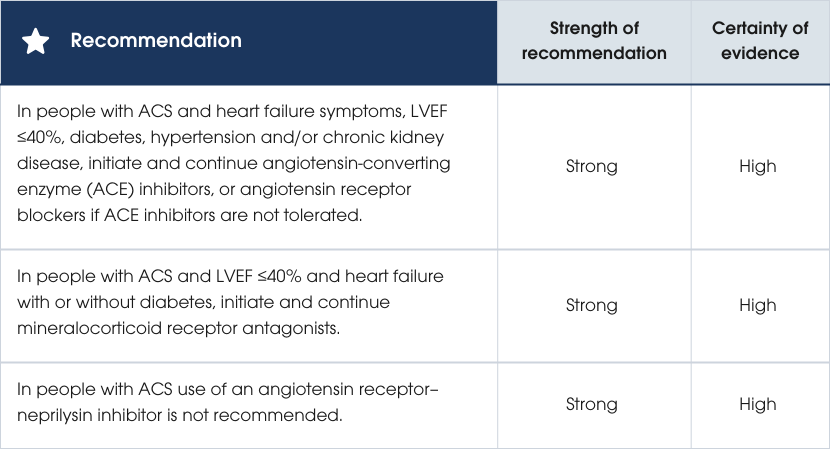

Evidence supporting the recommendations

Practice points

- In people with ACS and LVEF ≥40% or without clinical heart failure, consider use of ACE inhibitors (or angiotensin receptor blockers if ACE inhibitors not tolerated) to improve survival [527].

- For people with ACS and concurrent hypertension, ACE inhibitors and angiotensin receptor blockers are indicated as first-line agents for hypertension management. Current blood pressure management and targets are provided in the Heart Foundation’s Guideline for the diagnosis and management of hypertension in adults [530].

- In people with ACS and heart failure, ongoing management should align with the Guidelines for the prevention, detection and management of heart failure in Australia, with consideration of referral to specialised heart failure services to optimise care and improve outcomes [454].

Evidence supporting the recommendations

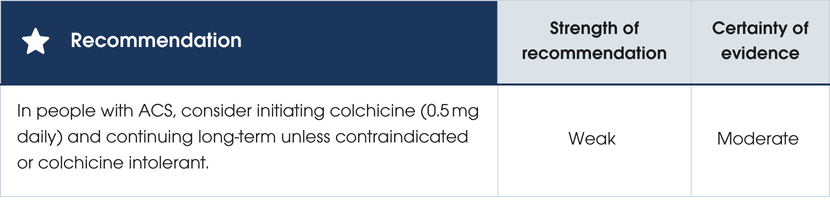

However, a subsequent trial of colchicine treatment post-MI showed no benefit to cardiovascular death, recurrent infarction, stroke or unplanned revascularisation over three years. Further meta-analyses are needed to clarify colchicine’s role post-ACS.

Semaglutide

Semaglutide, a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist, has demonstrated significant cardiovascular benefits in people with obesity. In the SELECT trial, which enrolled adults with established CVD, obesity (or overweight) and without diabetes, once-weekly subcutaneous semaglutide (2.4 mg) reduced the combined incidence of cardiovascular death, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or nonfatal stroke (hazard ratio 0.80; 95% CI 0.72–0.90) [533]. These findings highlight the potential of semaglutide as an adjunct treatment to facilitate weight loss and reduce cardiovascular risk, including secondary prevention in people with ACS who meet criteria for overweight or obesity.2. Hospital care and reperfusion

References