Staying alive: a history of CPR

Blog: 24 May 2023

In the event of a cardiac arrest, time is of the essence. Lifesaving interventions can often literally be the difference between life and death.

The most well-known intervention, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, or CPR as it's more commonly referred to, can more than double a person's chance of surviving a cardiac arrest.

CPR combines mouth-to-mouth ventilation and chest compressions and is performed when a person is unresponsive - not breathing, not moving, or with no pulse.

/>You may be interested to discover that when you're performing CPR, you aren't actually trying to restart the person's heart. What you are doing is helping to make sure blood containing oxygen is still being delivered to their brain and organs. The mouth-to-mouth provides the person’s lungs with oxygen. The chest compressions help keep the blood moving around the body by (crudely) copying what the heart does naturally, contract and relax.

This lifesaving action can help keep a person alive until further assistance (ambulance or medical professional) arrives and help make sure they have the best chance of a good recovery when their heart is restarted. However, the modern version of CPR has an interesting history. After all, as long as people have been losing consciousness, we've been trying to help revive them!

Where did CPR come from?

Some reports of early attempts at resuscitation go as far back as Ancient Egypt! In the 1500s, it was thought that hitting a person with a whip would shock them awake. The 1700s saw us hang people upside down to revive them, and in the 1800s people tried lying the person on the back of a trotting horse. There was even a time when bloodletting and blowing tobacco smoke into the person’s rectum was used to revive them!

Although some of these earlier attempts at resuscitation sound wacky to us now, there were also techniques that sound more familiar to us today.

Mouth-to-mouth breathing was first used in the 1700s as a way to revive a person who had drowned. In the 1880s, two physicians (Hall and Silvester) independently developed methods to compress the chest – lifting the person's arms to open their chest and then applying pressure to their chest to force them to exhale. Combining the compression of the chest and mouth-to-mouth was eventually published in a medical journal in 1960, and in 1963 the American Heart Foundation formally endorsed CPR.

Training in CPR has been happening all over the world since this time. In Australia, the training was initially only for healthcare professionals. But in 1973 the Royal Melbourne Hospital begun to offer training in CPR (called heart-lung resuscitation at the time) to the general public. During Heart Week in 1975, the Heart Foundation launched mobile training units that would travel the country to teach CPR.

In 1976 in Australia, the Australian Resuscitation Council was launched to standardise and promote the teaching of CPR throughout the country.

Who is Resusci-Annie?

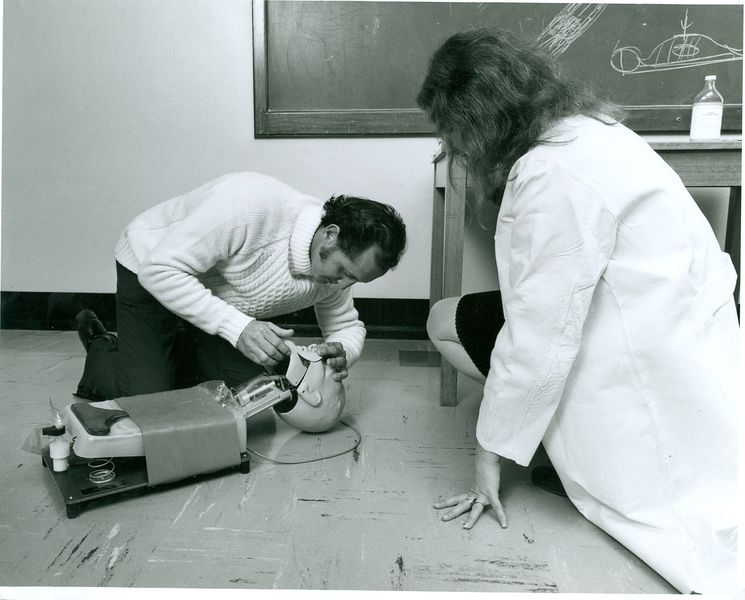

A familiar face in CPR training classes around the world is Resusci-Annie. If you haven’t met Resusci-Annie, she is the CPR doll that is used in training sessions to practice technique. Her familiar face was modelled from a woman who drowned in the river Seine in France in the 1880s, and it has been said by some that she is the most kissed woman in the world!

She was developed as a training tool for CPR that could provide feedback to the student with dials that showed the ventilation and compression pressure. Now she has a whole family of ‘colleagues’ – with mannikins available for infants and young children, as well as adults containing varying levels of technology.

Where is CPR at today?

Like all things, CPR has not remained static. Constant changes are being introduced to improve CPR, and consequently, survival rates.

In the 1980s the method was adapted for safe use on children and babies. In the 1990s defibrillators (devices that deliver an electric shock to the heart) begin to be introduced to the public for use along with CPR in resuscitating people who have had a cardiac arrest. In the 2010s the American Heart Association changed their recommendation on the speed and depth of chest compressions to make CPR safer. More recently, the global pandemic has prompted a shift towards hands-only CPR in some countries to help prevent spreading infection.

Where to next for CPR?

What happens if you don’t know how to do CPR?

In Australia, only a little over half (50%) of the population are trained to perform CPR. And over half of those people had their training more than 5 years ago. That means that in Australia, only 40% of people who have had a cardiac arrest receive CPR from a bystander while waiting for an ambulance.

CPR training in Australia is largely voluntary – other than for some professions such as teachers and fitness instructors. If you aren’t trained, or it is time for a refresher course, there are lots of companies that offer accredited CPR training.

If you are CPR trained, you can sign up to the GoodSAM app – it is currently used in VIC, SA and NSW and alerts registered CPR-trained users when someone nearby is in cardiac arrest. It is linked to 000 and sends an alert when an ambulance has been called to their location so the trained person can help till the ambulance arrives.

But don’t let that stop you from lending a hand if you see someone in need. If you see someone having a medical emergency, call 000, they will step you through what you need to do.

As the Australian Resuscitation Council states: “any attempt at resuscitation is better than no attempt!”

You might also be interested in...

Automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD or AICD)

An automated implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD) is a device that helps restore normal heart rhythms using electrical impulses to manage arrhythmias.

Australia to build world’s largest sudden cardiac arrest registry

Australian scientists will build the world’s largest-ever registry of sudden cardiac arrest deaths in a major bid to solve one of the most elusive and frightening mysteries of cardiovascular disease.

.jpg?width=560&height=auto&format=pjpg&auto=webp)

What is a cardiac arrest?

With immediate help a cardiac arrest can be survived. Learn what the signs of cardiac arrest are, why it’s different to a heart attack, and the steps you need to talk to help someone in cardiac arrest.

Last updated14 March 2024